Using Rx

Consider drawing a Marble-diagram

Draw a marble-diagram of the observable sequence you want to create. By drawing the diagram, you will get a clearer picture on what operator(s) to use.

A marble-diagram is a diagram that shows event occurring over time. A marble diagram contains both input and output sequences(s).

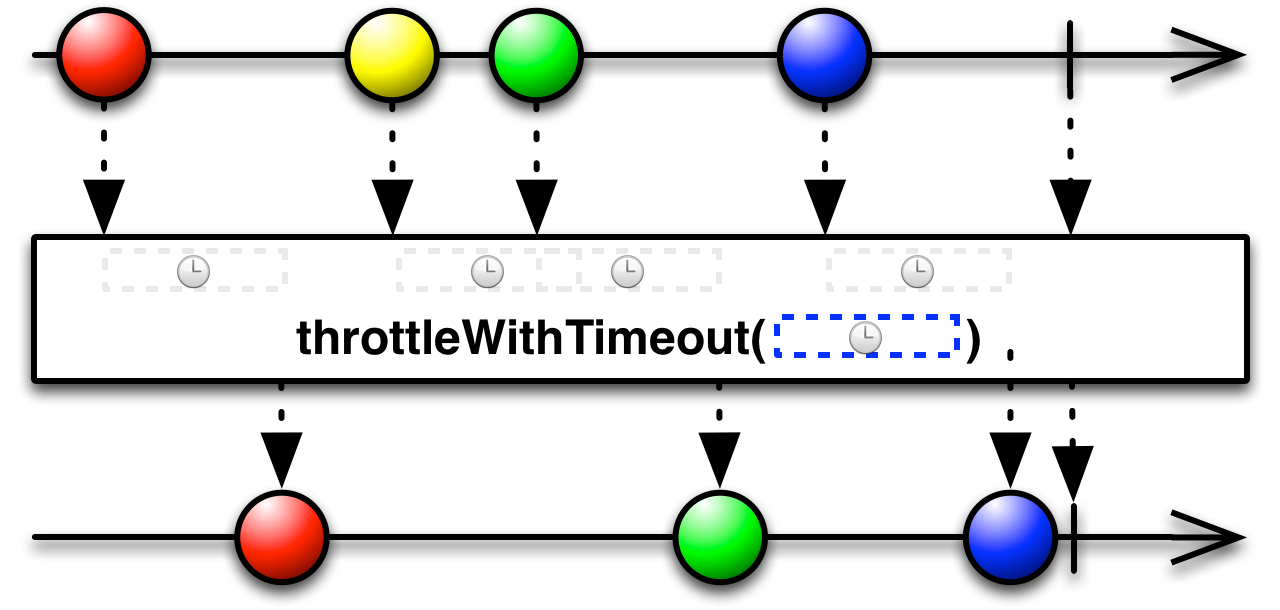

By drawing the diagram we can see that we will need some kind of delay after the user input, before firing of another asynchronous call. The delay in this sample maps to the throttle operator. To create another observable sequence from an observable sequence we will use the flatMap or selectMany operator. This

will lead to the following code:

var dictionarySuggest = userInput.throttle(250).flatMap(input => serverCall(input));

When to ignore this guideline

This guideline can be ignored if you feel comfortable enough with the observable sequence you want to write. However, even the Rx team members will still grab the whiteboard to draw a marble-diagram once in a while.

Consider passing multiple arguments to subscribe

For convenience, Rx provides an overload to the subscribe method that takes functions instead of an Observer argument.

The Observer object would require implementing all three methods (onNext, onError & onCompleted). The extensions to the subscribe method allow developers to use defaults chosen for each of these methods.

E.g. when calling the subscribe method that only has an onNext argument, the onError behavior will be to rethrow the exception on the thread that the message comes out from the observable sequence. The onCompleted behavior in this case is to do nothing.

In many situations, it is important to deal with the exception (either recover or abort the application gracefully).

Often it is also important to know that the observable sequence has completed successfully. For example, the application notifies the user that the operation has completed.

Because of this, it is best to provide all 3 arguments to the subscribe function.

RxJS also provides three convenience methods which only subscribe to the part of the sequence that is desired. The other handlers will default to their original behaviors. There are three of such functions:

subscribeOnNext: foronNextmessages onlysubscribeOnError: foronErrormessages onlysubscribeOnCompleted: foronCompletedmessages only.

When to ignore this guideline

- When the observable sequence is guaranteed not to complete, e.g. an event such as keyup.

- When the observable sequence is guaranteed not to have

onErrormessages (e.g. an event, a materialized observable sequence etc…). - When the default behavior is the desirable behavior.

Consider passing a specific scheduler to concurrency introducing operators

Rather than using the observeOn operator to change the execution context on which the observable sequence produces messages, it is better to create concurrency in the right place to begin with. As operators parameterize introduction of concurrency by providing a scheduler argument overload, passing the right scheduler will lead to fewer places where the ObserveOn operator has to be used.

Sample

Rx.Observable.range(0, 90000, Rx.Scheduler.requestAnimationFrame).subscribe(draw);

In this sample, callbacks from the range operator will arrive by calling window.requestAnimationFrame. The default overload of range would place the onNext call on the Rx.Scheduler.currentThread which is used when recursive scheduling is required immediately. By providing the Rx.Scheduler.requestAnimationFrame scheduler, all messages from this observable sequence will originiate on the window.requestAnimationFrame callback.

When to ignore this guideline

When combining several events that originate on different execution contexts, use guideline 4.4 to put all messages on a specific execution context as late as possible.

Call the observeOn operator as late and in as few places as possible

By using the observeOn operator, an action is scheduled for each message that comes through the original observable sequence. This potentially changes timing information as well as puts additional stress on the system. Placing this operator later in the query will reduce both concerns.

Sample

var result = xs.throttle(1000)

.flatMap(x => ys.takeUntil(zs).sample(250).map(y => x + y))

.merge(ws)

.filter(x => x < 10)

.observeOn(Rx.Scheduler.requestAnimationFrame);

This sample combines many observable sequences running on many different execution contexts. The query filters out a lot of messages. Placing the observeOn operator earlier in the query would do extra work on messages that would be filtered out anyway. Calling the observeOn operator at the end of the query will create the least performance impact.

When to ignore this guideline

Ignore this guideline if your use of the observable sequence is not bound to a specific execution context. In that case do not use the observeOn operator.

Consider limiting buffers

RxJS comes with several operators and classes that create buffers over observable sequences, e.g. the replay operator. As these buffers work on any observable sequence, the size of these buffers will depend on the observable sequence it is operating on. If the buffer is unbounded, this can lead to memory pressure. Many buffering operators provide policies to limit the buffer, either in time or size. Providing this limit will address memory pressure issues.

Sample

var result = xs.replay(null, 10000, 1000 * 60 /* 1 hr */).refCount();

In this sample, the replay operator creates a buffer. We have limited that buffer to contain at most 10,000 messages and keep these messages around for a maximum of 1 hour.

When to ignore this guideline

When the amount of messages created by the observable sequence that populates the buffer is small or when the buffer size is limited.

Make side-effects explicit using the do/tap operator

As many Rx operators take functions as arguments, it is possible to pass any valid user code in these arguments. This code can change global state (e.g. change global variables, write to disk etc...).

The composition in Rx runs through each operator for each subscription (with the exception of the sharing operators, such as publish). This will make every side-effect occur for each subscription.

If this behavior is the desired behavior, it is best to make this explicit by putting the side-effecting code

in a do/tap operator. There are overloads to this method which call the specified method only, for example doOnNext/tapOnNext, doOnError/tapOnError,doOnCompleted/tapOnCompleted

Sample

var result = xs.filter(x => x.failed).tap(x => log(x));

In this sample, messages are filtered for failure. The messages are logged before handing them out to the code subscribed to this observable sequence. The logging is a side-effect (e.g. placing the messages in the computer’s event log) and is explicitly done via a call to the do/tap operator.

Assume messages can come through until unsubscribe has completed

As RxJS uses a push model, messages can be sent from different execution contexts. Messages can be in flight while calling unsubscribe. These messages can still come through while the call to unsubscribe is in progress. After control has returned, no more messages will arrive. The unsubscription process can still be in progress on a different context.

When to ignore this guideline

Once the onCompleted or onError method has been received, the RxJS grammar guarantees that the subscription can be considered to be finished.

Use the publish operator to share side-effects

As many observable sequences are cold (see cold vs. hot on Channel 9), each subscription will have a

separate set of side-effects. Certain situations require that these side-effects occur only once. The publish operator provides a mechanism to share subscriptions by broadcasting a single subscription to multiple subscribers.

There are several overloads of the publish operator. The most convenient overloads are the ones that provide a function with a wrapped observable sequence argument that shares the side-effects.

Sample

var xs = Rx.Observable.create(observer => {

console.log('Side effect');

observer.onNext('hi!');

observer.onCompleted();

});

xs.publish(sharedXs => {

sharedXs.subscribe(console.log);

sharedXs.subscribe(console.log);

return sharedXs;

}).subscribe();

In this sample, xs is an observable sequence that has side-effects (writing to the console). Normally each separate subscription will trigger these side-effects. The publish operator uses a single subscription to xs for all subscribers to sharedXs.

When to ignore this guideline

Only use the publish operator to share side-effects when sharing is required. In most situations you can create separate subscriptions without any problems: either the subscriptions do not have side-effects or the side effects can execute multiple times without any issues.